What People Are Saying

“Knowledge is a consequence of experience.”

— Jean Piaget

“The role of the teacher is to create the conditions for invention rather than provide ready-made knowledge.”

— Seymour Papert

Reflective Journal #1

As I begin my first portfolio entry for the EDU T127 Teaching and Learning Lab Practicum (TLLP) course, I find myself reflecting on two concepts that feel especially central to my academic and professional journey: constructivism and constructionism. These theories not only frame how people learn but also resonate with my own experiences in classrooms and educational projects. Therefore, writing this post is a way for me to trace the connections between what I am learning at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) and the work I have done and will continue to do as a teacher and learning designer.

Relating

According to the course, constructivism, developed by Jean Piaget, is a theory of knowledge. It holds that people actively construct their own knowledge by building mental structures from their experiences, where learning is seen as an internal, cognitive process where learners organize and reorganize their beliefs and ideas as they encounter new situations (GSI Teaching & Resource Center, n.d.). Constructionism, advanced by Seymour Papert and rooted in Piaget’s ideas, is a theory of education which emphasizes that learning happens most powerfully when learners are engaged in making meaningful products—such as poems, programs, or models—because constructing things in the world simultaneously helps them construct knowledge in their minds (Falbel, n.d.). In other words, while constructivism highlights the internal construction of knowledge, constructionism underscores the importance of learning through making tangible artifacts that embody and reinforce understanding.

Reporting & Reasoning

These two concepts align closely with my learning experiences during my undergraduate studies at Shanghai International Studies University (SISU) and my graduate studies at HGSE. Looking back at my undergraduate years, I primarily learned in a constructivist way. For instance, when studying rhetorical devices in English, I often compared them to their Chinese counterparts and connected them to my prior knowledge of rhetorical strategies. By contrast, since beginning my graduate studies at HGSE—especially during the Fall Term—I have been enrolled in several courses that embody constructionist principles. In the TLLP course, for example, we engage in re-designing the online course How People Learn for a specific audience. In EDU T519 Digital Fabrication and Making in Education, we design learning toolkits for children using tools such as laser cutters, 3D printers, and sewing machines. Likewise, in EDU H801 Literacy Assessment and Intervention Practicum, we conduct literacy assessments in elementary schools in Cambridge and Boston and design targeted intervention plans to support learners’ literacy development. Collectively, these experiences have not only enriched my academic journey but also deepened my understanding of how constructivism and constructionism intersect in practice.

Based on these insights, I reflected on my previous experiences as a pre-service teacher and teaching practitioner. Among them, the one that stands out most is my internship during senior year at Shanghai Nanyang Model High School, where I successfully applied task-based language teaching (TBLT) to enhance students’ understanding of English writing. During this practicum, I unknowingly integrated both constructivist and constructionist principles into my teaching. For example, when introducing rhetorical devices, I encouraged students to interpret English advertising slogans, debate their meanings, and connect them to prior knowledge of rhetorical strategies—an approach grounded in the constructivist emphasis on sense-making. I then organized students into groups to design and present their own original advertising slogans, enabling them to embody their understanding of rhetoric in a tangible product that could be shared and critiqued—an instance of constructionist learning. At the time, I simply viewed this as an effective teaching practice, particularly since it received positive feedback from students, my mentor, and the school principal. Now, however, I recognize that the success of this lesson stemmed from the seamless integration of constructivist and constructionist approaches to teaching and learning.

Reconstructing

In conclusion, this reflection marks my first step in building a portfolio for the TLLP course, and it has helped me recognize how constructivism and constructionism have shaped both my past and present practices as a teacher and learner. Moving forward, I hope to continue applying these ideas intentionally in my TLLP project work, especially by designing learning experiences that invite learners to both make sense of new knowledge and create meaningful artifacts to represent their understanding. By keeping these two lenses in mind, I aim to not only refine my professional practice but also deepen my contributions as a reflective practitioner and learning designer at HGSE.

Learning by Reflecting

Learning by Reflecting

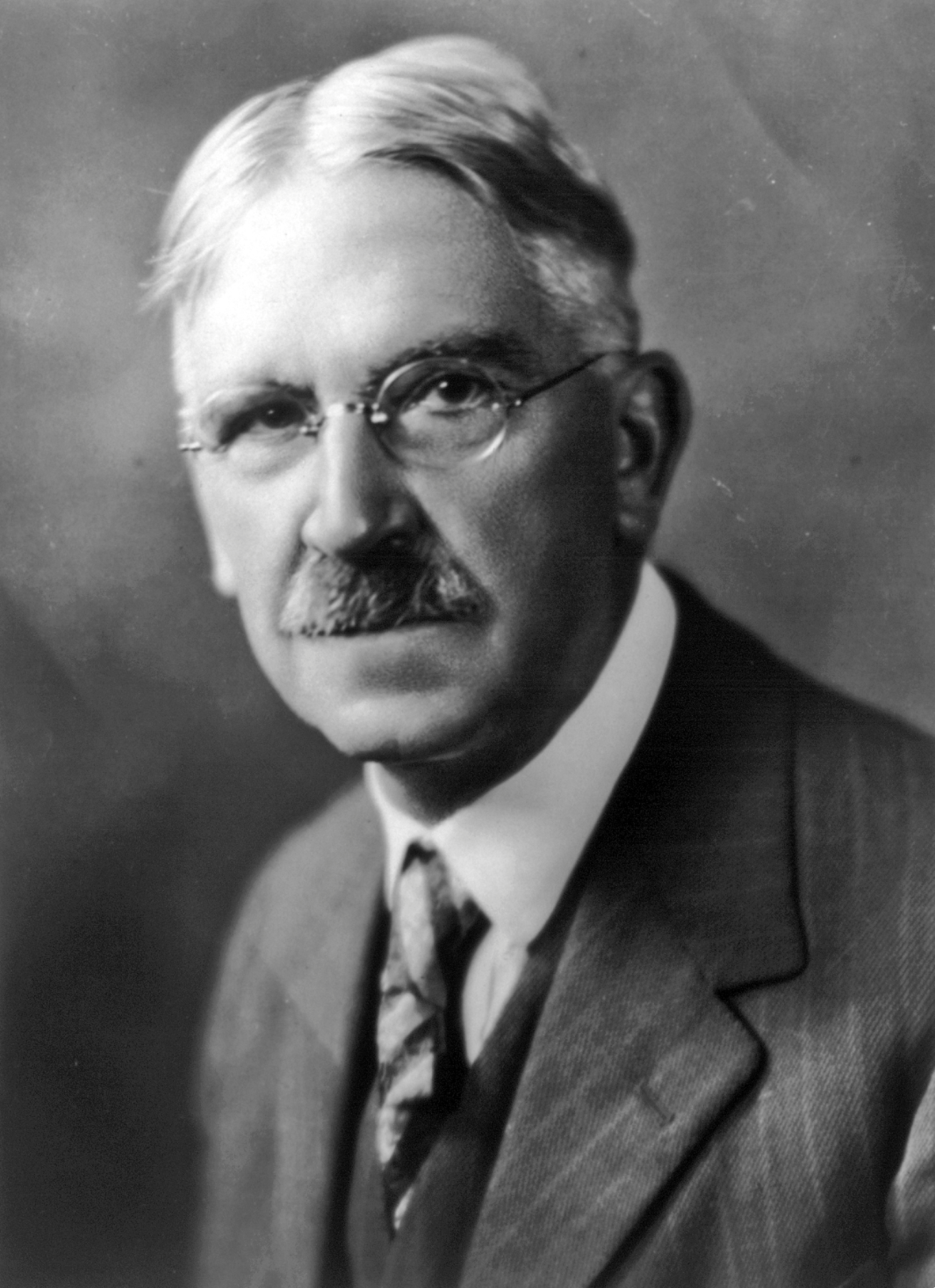

“Give the pupils something to do, not something to learn; and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking, learning naturally results.”

— John Dewey

-

Falbel, A. (n.d.). Constructionism. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

GSI Teaching & Resource Center. (n.d.). Social constructivism. UC Berkeley. Retrieved October 1, 2025, from https://gsi.berkeley.edu/gsi-guide-contents/learning-theory-research/social-constructivism/